OSI Transport Layer

Roles of the Transport Layer

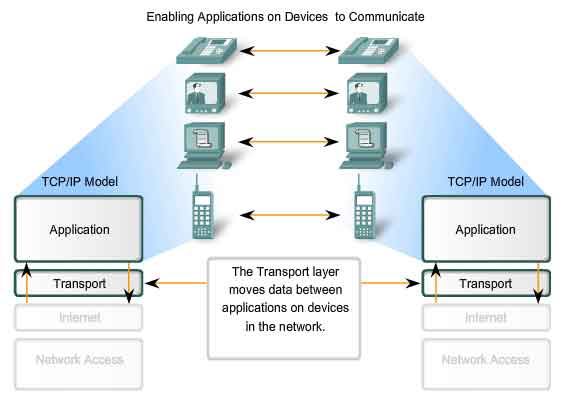

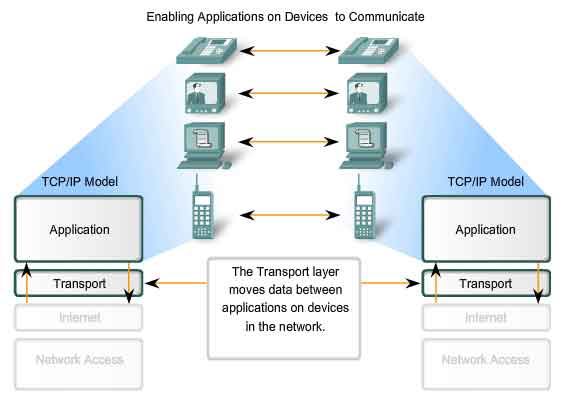

Purpose of the Transport Layer

The Transport layer provides for the segmentation of data and the

control necessary to reassemble these pieces into the various

communication streams. Its primary responsibilities to accomplish this

are:

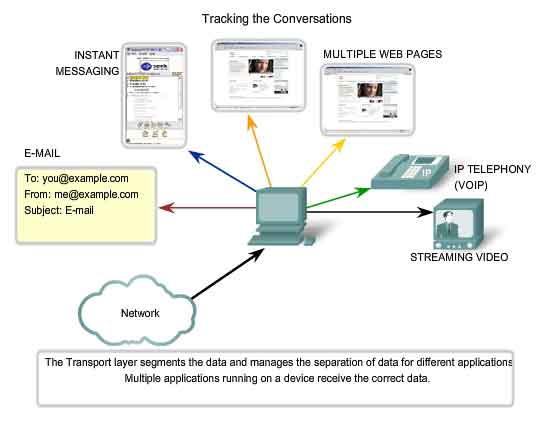

Tracking Individual Conversations

Any

host may have multiple applications that are communicating across the

network. Each of these applications will be communicating with one or

more applications on remote hosts. It is the responsibility of the

Transport layer to maintain the multiple communication streams between

these applications.

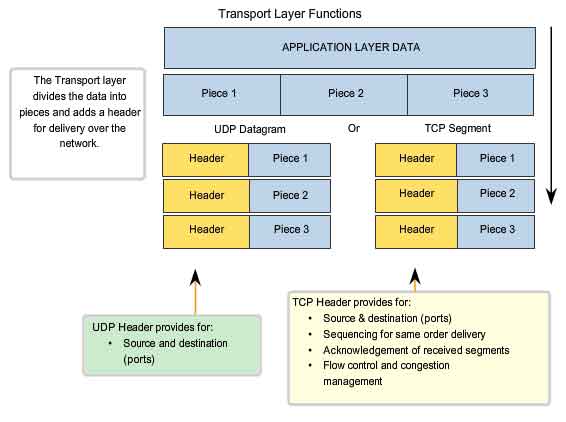

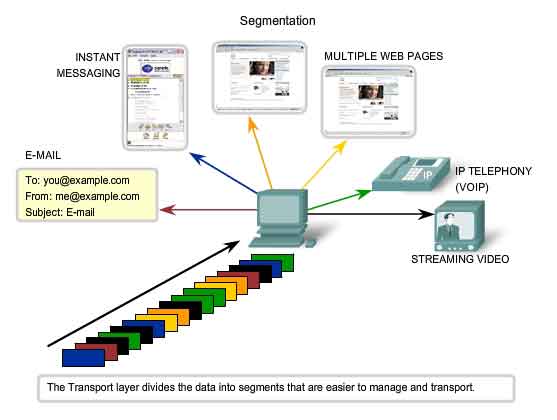

Segmenting Data

As

each application creates a stream data to be sent to a remote

application, this data must be prepared to be sent across the media in

manageable pieces. The Transport layer protocols describe services that

segment this data from the Application layer. This includes the

encapsulation required on each piece of data. Each piece of application

data requires headers to be added at the Transport layer to indicate to

which communication it is associated.

Reassembling Segments

At

the receiving host, each piece of data may be directed to the

appropriate application. Additionally, these individual pieces of data

must also be reconstructed into a complete data stream that is useful to

the Application layer. The protocols at the Transport layer describe

the how the Transport layer header information is used to reassemble the

data pieces into streams to be passed to the Application layer.

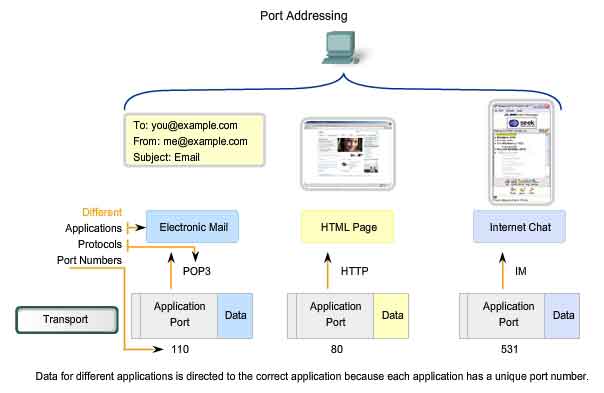

Identifying the Applications

In

order to pass data streams to the proper applications, the Transport

layer must identify the target application. To accomplish this, the

Transport layer assigns an application an identifier. The TCP/IP

protocols call this identifier a port number. Each software process that

needs to access the network is assigned a port number unique in that

host. This port number is used in the transport layer header to indicate

to which application that piece of data is associated. The Transport

layer is the link between the Application layer and the lower layer that

are responsible for network transmission. This layer accepts data from

different conversations and passes it down to the lower layers as

manageable pieces that can be eventually multiplexed over the media.

Applications do not need to know the operational details of the network

in use. The applications generate data that is sent from one application

to another, without regard to the destination host type, the type of

media over which the data must travel, the path taken by the data, the

congestion on a link, or the size of the network. Additionally, the

lower layers are not aware that there are multiple applications sending

data on the network. Their responsibility is to deliver data to the

appropriate device. The Transport layer then sorts these pieces before

delivering them to the appropriate application.

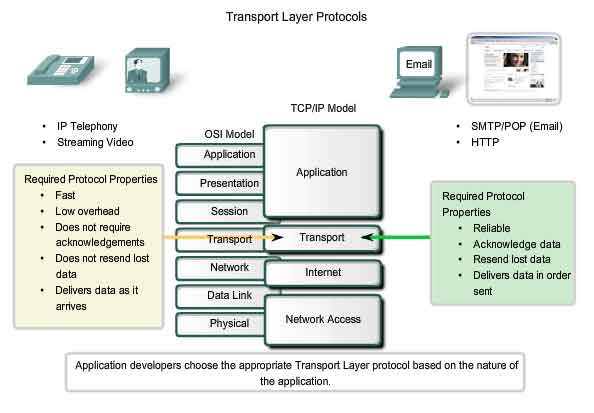

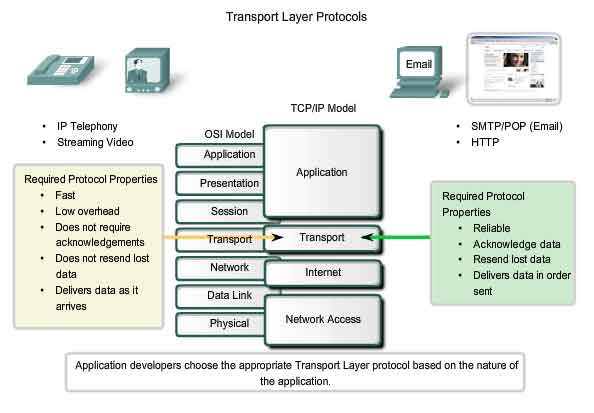

Data Requirements Vary

Because

different applications have different requirements, there are multiple

Transport layer protocols. For some applications, segments must arrive

in a very specific sequence in order to be processed successfully. In

some cases, all of the data must be received for any of it to be of use.

In other cases, an application can tolerate some loss of data during

transmission over the network. In today's converged networks,

applications with very different transport needs may be communicating on

the same network. The different Transport layer protocols have

different rules allowing devices to handle these diverse data

requirements. Some protocols provide just the basic functions for

efficiently delivering the data pieces between the appropriate

applications. These types of protocols are useful for applications whose

data is sensitive to delays. Other Transport layer protocols describe

processes that provide additional features, such as ensuring reliable

delivery between the applications. While these additional functions

provide more robust communication at the Transport layer between

applications, they have additional overhead and make larger demands on

the network.

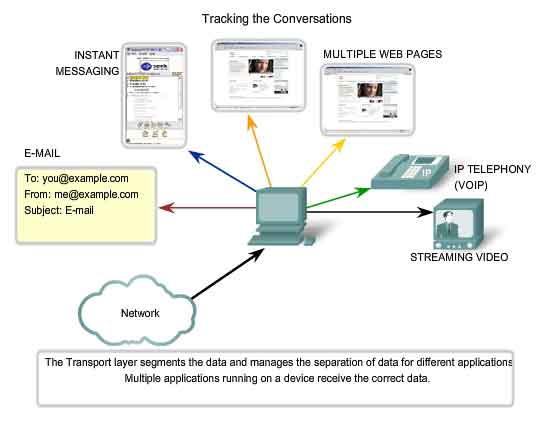

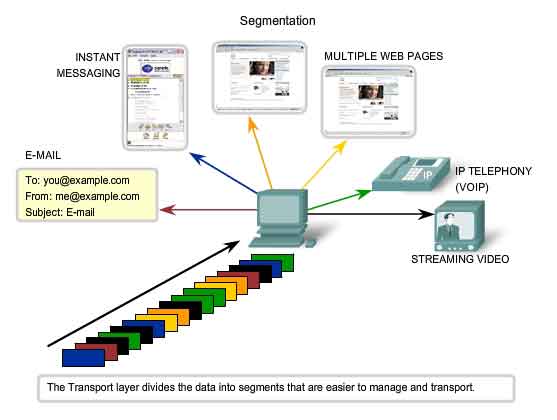

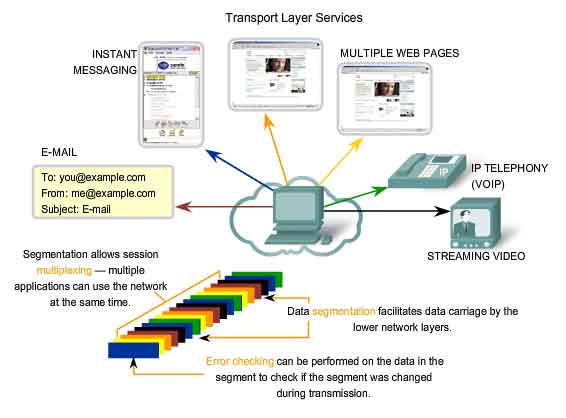

Separating Multiple Communications

Consider

a computer connected to a network that is simultaneously receiving and

sending e-mail and instant messages, viewing websites, and conducting a

VoIP phone call. Each of these applications is sending and receiving

data over the network at the same time. However, data from the phone

call is not directed to the web browser, and text from an instant

message does not appear in an e-mail. Further, users require that an

e-mail or web page be completely received and presented for the

information to be considered useful. Slight delays are considered

acceptable to ensure that the complete information is received and

presented. In contrast, occasionally missing small parts of a telephone

conversation might be considered acceptable. One can either infer the

missing audio from the context of the conversation or ask the other

person to repeat what they said. This is considered preferable to the

delays that would result from asking the network to manage and resend

missing segments. In this example, the user - not the network - manages

the resending or replacement of missing information.

As

explained in a previous chapter, sending some types of data - a video

for example - across a network as one complete communication stream

could prevent other communications from occurring at the same time. It

also makes error recovery and retransmission of damaged data difficult.

Dividing data into small parts, and sending these parts from the source

to the destination, enables many different communications to be

interleaved (multiplexed) on the same network. Segmentation of the data,

in accordance with Transport layer protocols, provides the means to

both send and receive data when running multiple applications

concurrently on a computer. Without segmentation, only one application,

the streaming video for example, would be able to receive data. You

could not receive e-mails, chat on instant messenger, or view web pages

while also viewing the video. At the Transport layer, each particular

set of pieces flowing between a source application and a destination

application is known as a conversation. To identify each segment of

data, the Transport layer adds to the piece a header containing binary

data. This header contains fields of bits. It is the values in these

fields that enable different Transport layer protocols to perform

different functions.

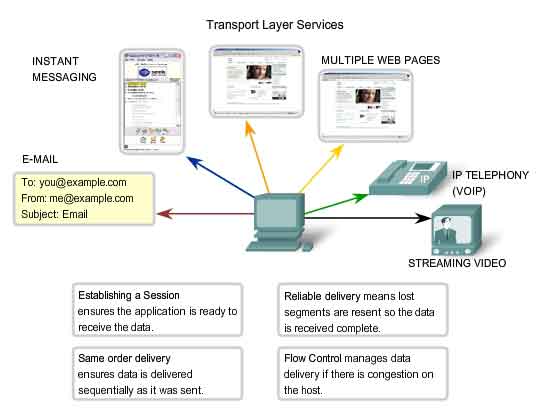

Controlling the Conversations

The primary functions specified by all Transport layer protocols include:

Segmentation and Reassembly

- Most networks have a limitation on the amount of data that can be

included in a single PDU. The Transport layer divides application data

into blocks of data that are an appropriate size. At the destination,

the Transport layer reassembles the data before sending it to the

destination application or service.

Conversation Multiplexing

- There may be many applications or services running on each host in

the network. Each of these applications or services is assigned an

address known as a port so that the Transport layer can determine with

which application or service the data is identified. In addition to

using the information contained in the headers, for the basic functions

of data segmentation and reassembly, some protocols at the Transport

layer provide:

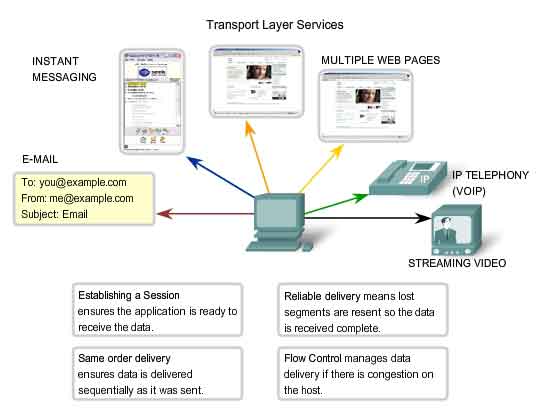

Establishing a Session

The

Transport layer can provide this connection orientation by creating a

sessions between the applications. These connections prepare the

applications to communicate with each other before any data is

transmitted. Within these sessions, the data for a communication between

the two applications can be closely managed.

Reliable Delivery

For

many reasons, it is possible for a piece of data to become corrupted,

or lost completely, as it is transmitted over the network. The Transport

layer can ensure that all pieces reach their destination by having the

source device to retransmit any data that is lost.

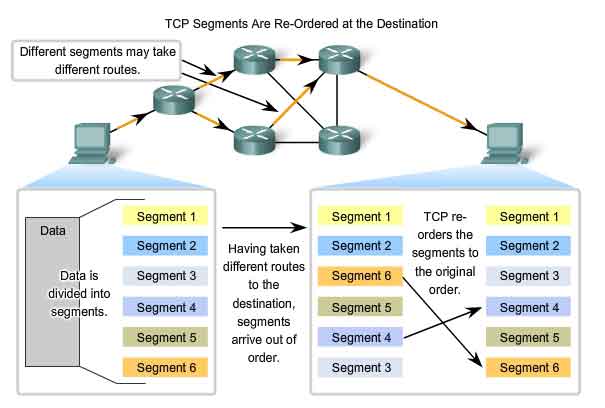

Same Order Delivery

Because

networks may provide multiple routes that can have different

transmission times, data can arrive in the wrong order. By numbering and

sequencing the segments, the Transport layer can ensure that these

segments are reassembled into the proper order.

Flow Control

Network

hosts have limited resources, such as memory or bandwidth. When

Transport layer is aware that these resources are overtaxed, some

protocols can request that the sending application reduce the rate of

data flow. This is done at the Transport layer by regulating the amount

of data the source transmits as a group. Flow control can prevent the

loss of segments on the network and avoid the need for retransmission.

Supporting Reliable Communication

Recall that the primary function of the Transport layer is to manage

the application data for the conversations between hosts. However,

different applications have different requirements for their data, and

therefore different Transport protocols have been developed to meet

these requirements. A Transport layer protocol can implement a method to

ensure reliable delivery of the data. In networking terms, reliability

means ensuring that each piece of data that the source sends arrives at

the destination. At the Transport layer the three basic operations of

reliability are:

This

requires the processes of Transport layer of the source to keep track

of all the data pieces of each conversation and the retransmit any of

data that did were not acknowledged by the destination. The Transport

layer of the receiving host must also track the data as it is received

and acknowledge the receipt of the data. These reliability processes

place additional overhead on the network resources due to the

acknowledgement, tracking, and retransmission. To support these

reliability operations, more control data is exchanged between the

sending and receiving hosts. This control information is contained in

the Layer 4 header. This creates a trade-off between the value of

reliability and the burden it places on the network. Application

developers must choose which transport protocol type is appropriate

based on the requirements of their applications. At the Transport layer,

there are protocols that specify methods for either reliable,

guaranteed delivery or best-effort delivery. In the context of

networking, best-effort delivery is referred to as unreliable, because

there is no acknowledgement that the data is received at the

destination.

Determining the Need for Reliability

Applications,

such as databases, web pages, and e-mail, require that all of the sent

data arrive at the destination in its original condition, in order for

the data to be useful. Any missing data could cause a corrupt

communication that is either incomplete or unreadable. Therefore, these

applications are designed to use a Transport layer protocol that

implements reliability. The additional network overhead is considered to

be required for these applications. Other applications are more

tolerant of the loss of small amounts of data. For example, if one or

two segments of a video stream fail to arrive, it would only create a

momentary disruption in the stream. This may appear as distortion in the

image but may not even be noticeable to the user. Imposing overhead to

ensure reliability for this application could reduce the usefulness of

the application. The image in a streaming video would be greatly

degraded if the destination device had to account for lost data and

delay the stream while waiting for its arrival. It is better to render

the best image possible at the time with the segments that arrive and

forego reliability. If reliability is required for some reason, these

applications can provide error checking and retransmission requests.

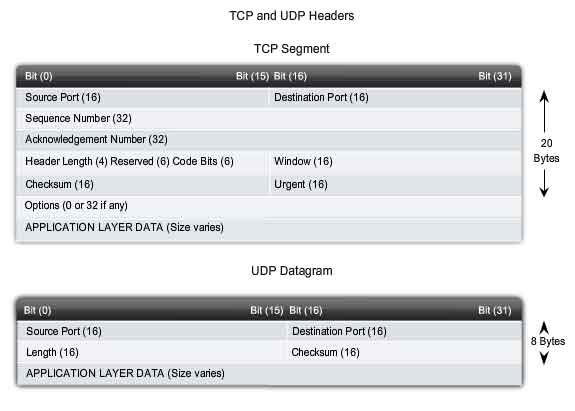

TCP and UDP

The two most common Transport layer protocols of TCP/IP protocol suite

are Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol

(UDP). Both protocols manage the communication of multiple applications.

The differences between the two are the specific functions that each

protocol implements.

User Datagram Protocol (UDP)

UDP

is a simple, connectionless protocol, described in RFC 768. It has the

advantage of providing for low overhead data delivery. The pieces of

communication in UDP are called datagrams. These datagrams are sent as

"best effort" by this Transport layer protocol.

Applications that use UDP include: Domain Name System (DNS), Video Streaming, Voice over IP (VoIP)

Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)

TCP

is a connection-oriented protocol, described in RFC 793. TCP incurs

additional overhead to gain functions. Additional functions specified by

TCP are the same order delivery, reliable delivery, and flow control.

Each TCP segment has 20 bytes of overhead in the header encapsulating

the Application layer data, whereas each UDP segment only has 8 bytes of

overhead. See the figure for a comparison.

Applications that use TCP are: Web Browsers, E-mail, File Transfers

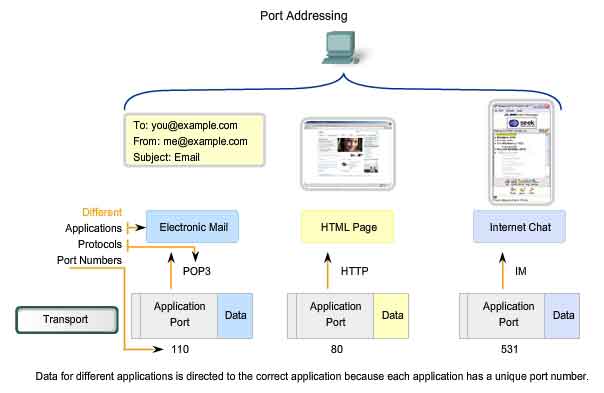

Port Addressing

Identifying the Conversations

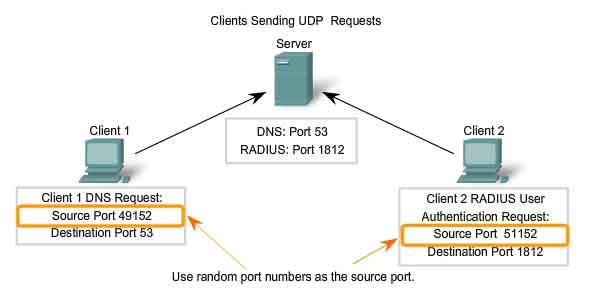

Consider

the earlier example of a computer simultaneously receiving and sending

e-mail, instant messages, web pages, and a VoIP phone call. The TCP and

UDP based services keep track of the various applications that are

communicating. To differentiate the segments and datagrams for each

application, both TCP and UDP have header fields that can uniquely

identify these applications. These unique identifiers are the port

numbers. In the header of each segment or datagram, there is a source

and destination port. The source port number is the number for this

communication associated with the originating application on the local

host. The destination port number is the number for this communication

associated with the destination application on the remote host. Port

numbers are assigned in various ways, depending on whether the message

is a request or a response. While server processes have static port

numbers assigned to them, clients dynamically choose a port number for

each conversation. When a client application sends a request to a server

application, the destination port contained in the header is the port

number that is assigned to the service daemon running on the remote

host. The client software must know what port number is associated with

the server process on the remote host. This destination port number is

configured, either by default or manually. For example, when a web

browser application makes a request to a web server, the browser uses

TCP and port number 80 unless otherwise specified. This is because TCP

port 80 is the default port assigned to web-serving applications. Many

common applications have default port assignments. The source port in a

segment or datagram header of a client request is randomly generated. As

long as it does not conflict with other ports in use on the system, the

client can choose any port number. This port number acts like a return

address for the requesting application. The Transport layer keeps track

of this port and the application that initiated the request so that when

a response is returned, it can be forwarded to the correct application.

The requesting application port number is used as the destination port

number in the response coming back from the server. The combination of

the Transport layer port number and the Network layer IP address

assigned to the host uniquely identifies a particular process running on

a specific host device. This combination is called a socket.

Occasionally, you may find the terms port number and socket used

interchangeably. In the context of this course, the term socket refers

only to the unique combination of IP address and port number. A socket

pair, consisting of the source and destination IP addresses and port

numbers, is also unique and identifies the conversation between the two

hosts. For example, an HTTP web page request being sent to a web server

(port 80) running on a host with a Layer 3 IPv4 address of 192.168.1.20

would be destined to socket 192.168.1.20:80. If the web browser

requesting the web page is running on host 192.168.100.48 and the

Dynamic port number assigned to the web browser is 49152, the socket for

the web page would be 192.168.100.48:49152.

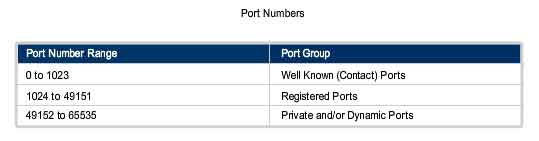

The

Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) assigns port numbers. IANA

is a standards body that is responsible for assigning various addressing

standards.

There are different types of port numbers:

Well Known Ports

(Numbers 0 to 1023) - These numbers are reserved for services and

applications. They are commonly used for applications such as HTTP (web

server) POP3/SMTP (e-mail server) and Telnet. By defining these

well-known ports for server applications, client applications can be

programmed to request a connection to that specific port and its

associated service.

Registered Ports

(Numbers 1024 to 49151) - These port numbers are assigned to user

processes or applications. These processes are primarily individual

applications that a user has chosen to install rather than common

applications that would receive a Well Known Port. When not used for a

server resource, these ports may also be used dynamically selected by a

client as its source port.

Dynamic or Private Ports

(Numbers 49152 to 65535) - Also known as Ephemeral Ports, these are

usually assigned dynamically to client applications when initiating a

connection. It is not very common for a client to connect to a service

using a Dynamic or Private Port (although some peer-to-peer file sharing

programs do).

Using both TCP and UDP

Some

applications may use both TCP and UDP. For example, the low overhead of

UDP enables DNS to serve many client requests very quickly. Sometimes,

however, sending the requested information may require the reliability

of TCP. In this case, the well known port number of 53 is used by both

protocols with this service.

Links

A current list of port numbers can be found at

http://www.iana.org/assignments/port-numbers.

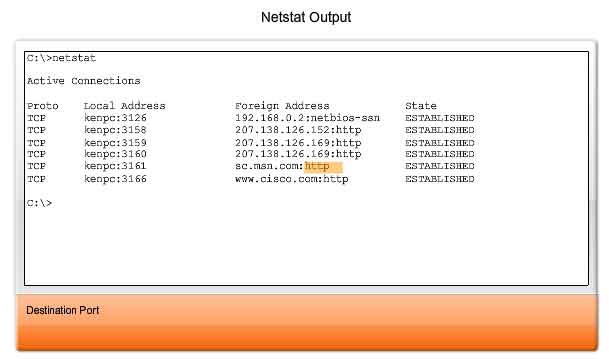

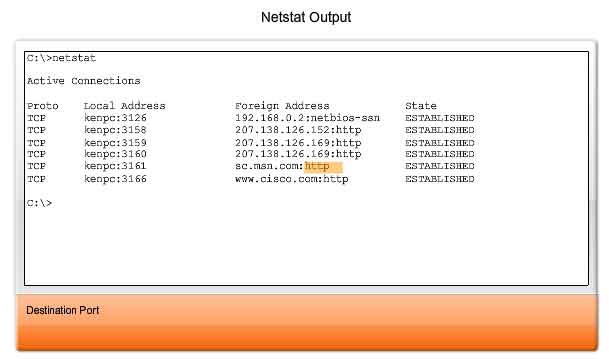

Sometimes it is necessary to know which active TCP connections are open and running on a networked host. Netstat is an important network utility that can be used to verify those connections. Netstat

lists the protocol in use, the local address and port number, the

foreign address and port number, and the state of the connection.

Unexplained TCP connections can pose a major security threat. This is

because they can indicate that something or someone is connected to the

local host. Additionally, unnecessary TCP connections can consume

valuable system resources thus slowing down the host's performance. Netstat

should be used to examine the open connections on a host when

performance appears to be compromised. Many useful options are available

for the netstat command.

Segmentation and Reassembly - Divide and Conquer

A previous chapter explained how PDUs are built by passing data from

an application down through the various protocols to create a PDU that

is then transmitted on the medium. At the destination host, this process

is reversed until the data can be passed up to the application. Some

applications transmit large amounts of data - in some cases, many

gigabytes. It would be impractical to send all of this data in one large

piece. No other network traffic could be transmitted while this data

was being sent. A large piece of data could take minutes or even hours

to send. In addition, if there were any error, the entire data file

would have to be lost or resent. Network devices would not have memory

buffers large enough to store this much data while it is transmitted or

received. The limit varies depending on the networking technology and

specific physical medium being in use.

Dividing

application data into pieces both ensures that data is transmitted

within the limits of the media and that data from different applications

can be multiplexed on to the media.

TCP and UDP Handle Segmentation Differently.

In

TCP, each segment header contains a sequence number. This sequence

number allows the Transport layer functions on the destination host to

reassemble segments in the order in which they were transmitted. This

ensures that the destination application has the data in the exact form

the sender intended. Although services using UDP also track the

conversations between applications, they are not concerned with the

order in which the information was transmitted, or in maintaining a

connection. There is no sequence number in the UDP header. UDP is a

simpler design and generates less overhead than TCP, resulting in a

faster transfer of data. Information may arrive in a different order

than it was transmitted because different packets may take different

paths through the network. An application that uses UDP must tolerate

the fact that data may not arrive in the order in which it was sent.

The TCP Protocol - Communicating with Reliability

TCP - Making Conversations Reliable

The key distinction between TCP and UDP is reliability. The

reliability of TCP communication is performed using connection-oriented

sessions. Before a host using TCP sends data to another host, the

Transport layer initiates a process to create a connection with the

destination. This connection enables the tracking of a session, or

communication stream between the hosts. This process ensures that each

host is aware of and prepared for the communication. A complete TCP

conversation requires the establishment of a session between the hosts

in both directions. After a session has been established, the

destination sends acknowledgements to the source for the segments that

it receives. These acknowledgements form the basis of reliability within

the TCP session. As the source receives an acknowledgement, it knows

that the data has been successfully delivered and can quit tracking that

data. If the source does not receive an acknowledgement within a

predetermined amount of time, it retransmits that data to the

destination. Part of the additional overhead of using TCP is the network

traffic generated by acknowledgements and retransmissions. The

establishment of the sessions creates overhead in the form of additional

segments being exchanged. There is also additional overhead on the

individual hosts created by the necessity to keep track of which

segments are awaiting acknowledgement and by the retransmission process.

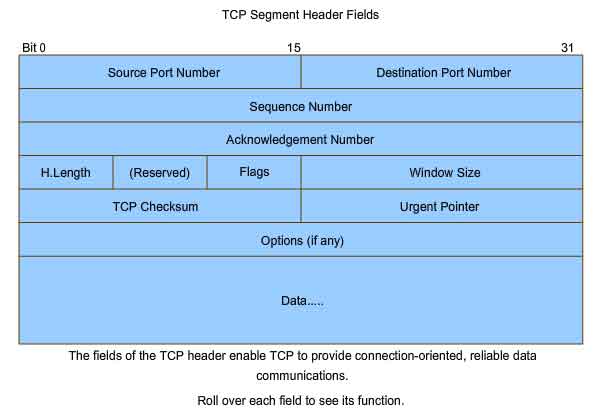

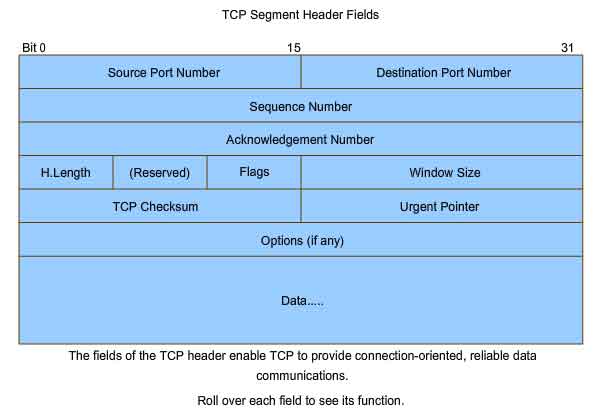

This reliability is achieved by having fields in the TCP segment, each

with a specific function, as shown in the figure. These fields will be

discussed later in this section.

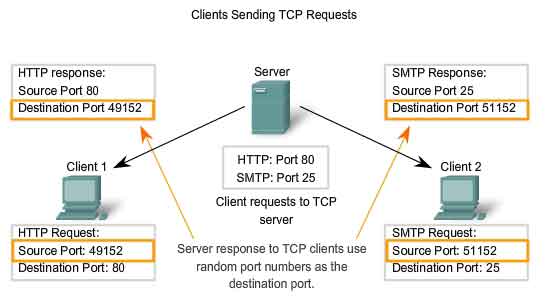

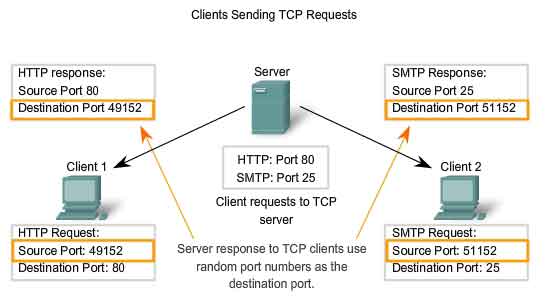

TCP Server Processes

As discussed in the previous chapter, application processes run on

servers. These processes wait until a client initiates communication

with a request for information or other services. Each application

process running on the server is configured to use a port number, either

by default or manually by a system administrator. An individual server cannot have two services assigned to the same port number within the same Transport layer services. A

host running a web server application and a file transfer application

cannot have both configured to use the same port (for example, TCP port

8080). When an active server application is assigned to a specific port,

that port is considered to be "open" on the server. This means that the

Transport layer accepts and processes segments addressed to that port.

Any incoming client request addressed to the correct socket is accepted

and the data is passed to the server application. There can be many

simultaneous ports open on a server, one for each active server

application. It is common for a server to provide more than one service,

such as a web server and an FTP server, at the same time. One way to

improve security on a server is to restrict server access to only those

ports associated with the services and applications that should be

accessible to authorized requestors. The figure shows the typical

allocation of source and destination ports in TCP client/server

operations.

TCP Connection Establishment and Termination

When two hosts communicate using TCP, a connection is established

before data can be exchanged. After the communication is completed, the

sessions are closed and the connection is terminated. The connection and

session mechanisms enable TCP's reliability function.

The

host tracks each data segment within a session and exchanges

information about what data is received by each host using the

information in the TCP header. Each connection represents two one-way

communication streams, or sessions. To establish the connection, the

hosts perform a three-way handshake. Control bits in the TCP header

indicate the progress and status of the connection. The three-way handshake:

In

TCP connections, the host serving as a client initiates the session to

the server. The three steps in TCP connection establishment are:

1.

The initiating client sends a segment containing an initial sequence

value, which serves as a request to the server to begin a communications

session.

2.

The server responds with a segment containing an acknowledgement value

equal to the received sequence value plus 1, plus its own synchronizing

sequence value. The value is one greater than the sequence number

because the ACK is always the next expected Byte or Octet. This

acknowledgement value enables the client to tie the response back to the

original segment that it sent to the server.

3.

Initiating client responds with an acknowledgement value equal to the

sequence value it received plus one. This completes the process of

establishing the connection.

To

understand the three-way handshake process, it is important to look at

the various values that the two hosts exchange. Within the TCP segment

header, there are six 1-bit fields that contain control information used

to manage the TCP processes. Those fields are:

URG - Urgent pointer field significant

ACK - Acknowledgement field significant

PSH - Push function

RST - Reset the connection

SYN - Synchronize sequence numbers

FIN - No more data from sender

These

fields are referred to as flags, because the value of one of these

fields is only 1 bit and, therefore, has only two values: 1 or 0. When a

bit value is set to 1, it indicates what control information is

contained in the segment.

Using a four-step process, flags are exchanged to terminate a TCP connection.

TCP Three-Way Handshake

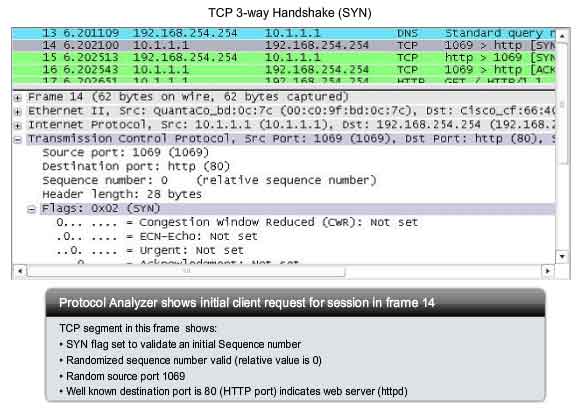

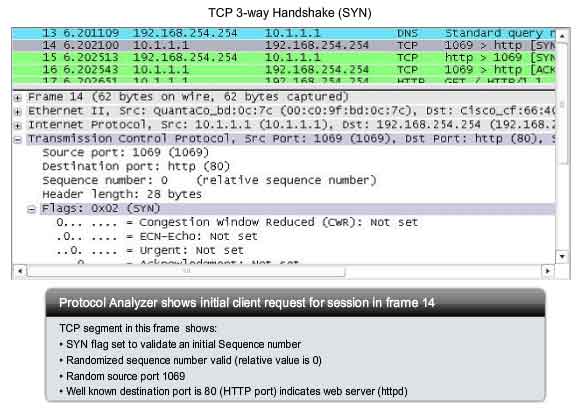

Using the Wireshark outputs, you can examine the operation of the TCP 3-way handshake:

Step 1

A

TCP client begins the three-way handshake by sending a segment with the

SYN (Synchronize Sequence Number) control flag set, indicating an

initial value in the sequence number field in the header. This initial

value for the sequence number, known as the Initial Sequence Number

(ISN), is randomly chosen and is used to begin tracking the flow of data

from the client to the server for this session. The ISN in the header

of each segment is increased by one for each byte of data sent from the

client to the server as the data conversation continues. As shown in the

figure, output from a protocol analyzer shows the SYN control flag and

the relative sequence number. The SYN control flag is set and the

relative sequence number is at 0. Although the protocol analyzer in the

graphic indicates the relative values for the sequence and

acknowledgement numbers, the true values are 32 bit binary numbers. We

can determine the actual numbers sent in the segment headers by

examining the Packet Bytes pane. Here you can see the four bytes

represented in hexadecimal.

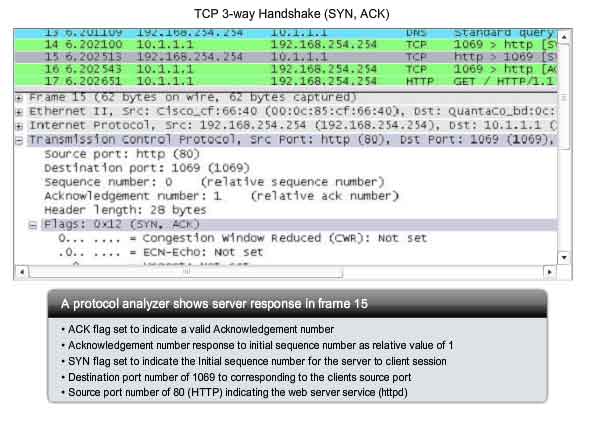

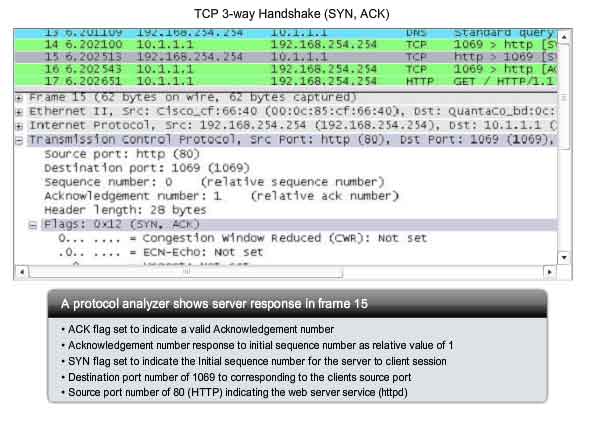

Step 2

The

TCP server needs to acknowledge the receipt of the SYN segment from the

client to establish the session from the client to the server. To do

so, the server sends a segment back to the client with the ACK flag set

indicating that the Acknowledgment number is significant. With this flag

set in the segment, the client recognizes this as an acknowledgement

that the server received the SYN from the TCP client. The value of the

acknowledgment number field is equal to the client initial sequence

number plus 1. This establishes a session from the client to the server.

The ACK flag will remain set for the balance of the session. Recall

that the conversation between the client and the server is actually two

one-way sessions: one from the client to the server, and the other from

the server to the client. In this second step of the three-way

handshake, the server must initiate the response from the server to the

client. To start this session, the server uses the SYN flag in the same

way that the client did. It sets the SYN control flag in the header to

establish a session from the server to the client. The SYN flag

indicates that the initial value of the sequence number field is in the

header. This value will be used to track the flow of data in this

session from the server back to the client. As shown in the figure, the

protocol analyzer output shows that the ACK and SYN control flags are

set and the relative sequence and acknowledgement numbers are shown.

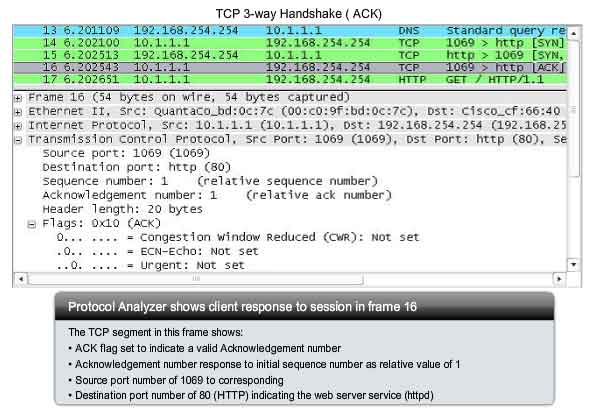

Step 3

Finally,

the TCP client responds with a segment containing an ACK that is the

response to the TCP SYN sent by the server. There is no user data in

this segment. The value in the acknowledgment number field contains one

more than the initial sequence number received from the server. Once

both sessions are established between client and server, all additional

segments exchanged in this communication will have the ACK flag set. As

shown in the figure, the protocol analyzer output shows the ACK control

flag set and the relative sequence and acknowledgement numbers are

shown.

Security can be added to the data network by:

This security can be implemented for all TCP sessions or only for selected sessions.

TCP Session Termination

To close a connection, the FIN (Finish) control flag in the segment

header must be set. To end each one-way TCP session, a two-way handshake

is used, consisting of a FIN segment and an ACK segment. Therefore, to

terminate a single conversation supported by TCP, four exchanges are

needed to end both sessions. Note: In this explanation, the terms

client and server are used in this description as a reference for

simplicity, but the termination process can be initiated by any two

hosts that complete the session:

1. When the client has no more data to send in the stream, it sends a segment with the FIN flag set.

2. The server sends an ACK to acknowledge the receipt of the FIN to terminate the session from client to server.

3. The server sends a FIN to the client, to terminate the server to client session.

4. The client responds with an ACK to acknowledge the FIN from the server.

When

the client end of the session has no more data to transfer, it sets the

FIN flag in the header of a segment. Next, the server end of the

connection will send a normal segment containing data with the ACK flag

set using the acknowledgment number, confirming that all the bytes of

data have been received. When all segments have been acknowledged, the

session is closed. The session in the other direction is closed using

the same process. The receiver indicates that there is no more data to

send by setting the FIN flag in the header of a segment sent to the

source. A return acknowledgement confirms that all bytes of data have

been received and that session is, in turn, closed. As shown in the

figure, the FIN and ACK control flags are set in the segment header,

thereby closing a HTTP session.

It

is also possible to terminate the connection by a three-way handshake.

When the client has no more data to send, it sends a FIN to the server.

If the server also has no more data to send, it can reply with both the

FIN and ACK flags set, combining two steps into one. The client replies with an ACK.

Managing TCP Sessions

TCP Segment Reassembly

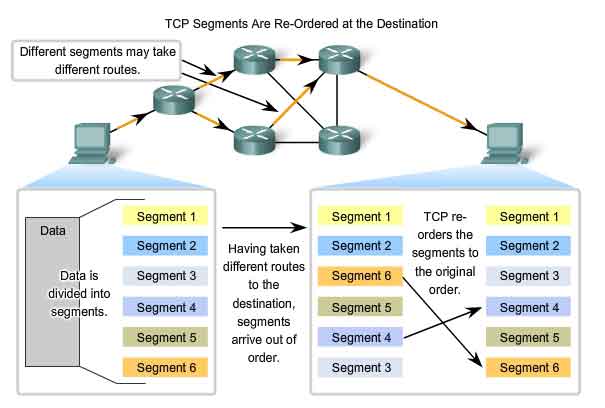

Resequencing Segments to Order Transmitted

When

services send data using TCP, segments may arrive at their destination

out of order. For the original message to be understood by the

recipient, the data in these segments is reassembled into the original

order. Sequence numbers are assigned in the header of each packet to

achieve this goal. During session setup, an initial sequence number

(ISN) is set. This initial sequence number represents the starting value

for the bytes for this session that will be transmitted to the

receiving application. As data is transmitted during the session, the

sequence number is incremented by the number of bytes that have been

transmitted. This tracking of data byte enables each segment to be

uniquely identified and acknowledged. Missing segments can be

identified. Segment sequence numbers enable reliability by indicating

how to reassemble and reorder received segments, as shown in the figure.

The receiving TCP process places the data from a segment into a

receiving buffer. Segments are placed in the proper sequence number

order and passed to the Application layer when reassembled. Any segments

that arrive with noncontiguous sequence numbers are held for later

processing. Then, when the segments with the missing bytes arrive, these

segments are processed.

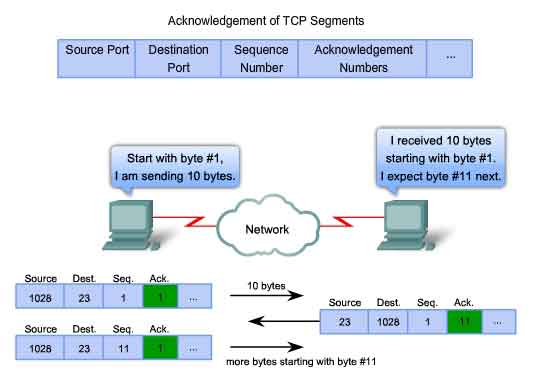

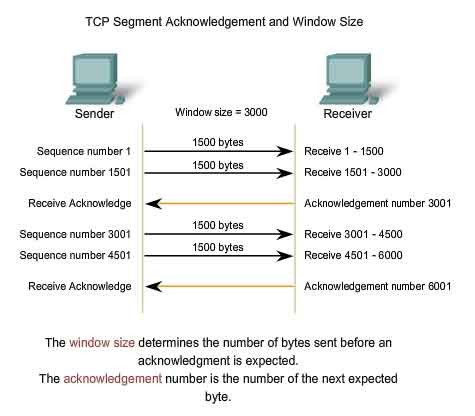

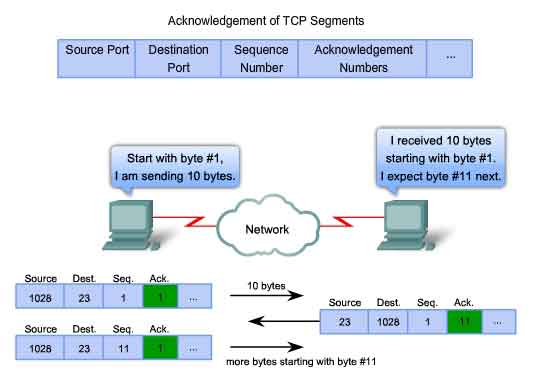

TCP Acknowledgement with Windowing

Confirming Receipt of Segments

One

of TCP's functions is making sure that each segment reaches its

destination. The TCP services on the destination host acknowledge the

data that it has received to the source application. The segment header

sequence number and acknowledgement number are used together to confirm

receipt of the bytes of data contained in the segments. The sequence

number is the relative number of bytes that have been transmitted in

this session plus 1 (which is the number of the first data byte in the

current segment). TCP uses the acknowledgement number in segments sent

back to the source to indicate the next byte in this session that the

receiver expects to receive. This is called expectational acknowledgement.

The source is informed that the destination has received all bytes in

this data stream up to, but not including, the byte indicated by the

acknowledgement number. The sending host is expected to send a segment

that uses a sequence number that is equal to the acknowledgement number.

Remember, each connection is actually two one-way sessions. Sequence

numbers and acknowledgement numbers are being exchanged in both

directions. In the example in the figure, the host on the left is

sending data to the host on the right. It sends a segment containing 10

bytes of data for this session and a sequence number equal to 1 in the

header. The receiving host on the right receives the segment at Layer 4

and determines that the sequence number is 1 and that it has 10 bytes of

data. The host then sends a segment back to the host on the left to

acknowledge the receipt of this data. In this segment, the host sets the

acknowledgement number to 11 to indicate that the next byte of data it

expects to receive in this session is byte number 11. When the sending

host on the left receives this acknowledgement, it can now send the next

segment containing data for this session starting with byte number 11.

Looking at this example, if the sending host had to wait for

acknowledgement of the receipt of each 10 bytes, the network would have a

lot of overhead. To reduce the overhead of these acknowledgements,

multiple segments of data can be sent before and acknowledged with a

single TCP message in the opposite direction. This acknowledgement

contains an acknowledgement number based on the total number of bytes

received in the session. For example, starting with a sequence number of

2000, if 10 segments of 1000 bytes each were received, an

acknowledgement number of 12001 would be returned to the source. The

amount of data that a source can transmit before an acknowledgement must

be received is called the window size. Window Size is a field in the

TCP header that enables the management of lost data and flow control.

TCP Retransmission

Handling Segment Loss

No

matter how well designed a network is, data loss will occasionally

occur. Therefore, TCP provides methods of managing these segment losses.

Among these is a mechanism to retransmit segments with unacknowledged

data. A destination host service using TCP usually only acknowledges

data for contiguous sequence bytes. If one or more segments are missing,

only the data in the segments that complete the stream are

acknowledged. For example, if segments with sequence numbers 1500 to

3000 and 3400 to 3500 were received, the acknowledgement number would be

3001. This is because there are segments with the sequence numbers 3001

to 3399 that have not been received. When TCP at the source host has

not received an acknowledgement after a predetermined amount of time, it

will go back to the last acknowledgement number that it received and

retransmit data from that point forward. The retransmission process is

not specified by the RFC, but is left up to the particular

implementation of TCP. For a typical TCP implementation, a host may

transmit a segment, put a copy of the segment in a retransmission queue,

and start a timer. When the data acknowledgment is received, the

segment is deleted from the queue. If the acknowledgment is not received

before the timer expires, the segment is retransmitted. The animation

demonstrates the retransmission of lost segments. Hosts today may also

employ an optional feature called Selective Acknowledgements. If

both hosts support Selective Acknowledgements, it is possible for the

destination to acknowledge bytes in discontinuous segments and the host

would only need to retransmit the missing data.

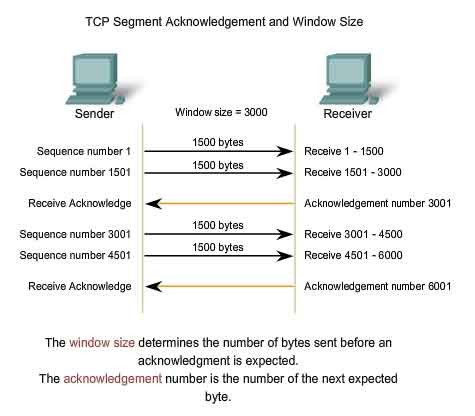

TCP Congestion Control - Minimizing Segment Loss

Flow Control

TCP

also provides mechanisms for flow control. Flow control assists the

reliability of TCP transmission by adjusting the effective rate of data

flow between the two services in the session. When the source is

informed that the specified amount of data in the segments is received,

it can continue sending more data for this session. This Window Size

field in the TCP header specifies the amount of data that can be

transmitted before an acknowledgement must be received. The initial

window size is determined during the session startup via the three-way

handshake. TCP feedback mechanism adjusts the effective rate of data

transmission to the maximum flow that the network and destination device

can support without loss. TCP attempts to manage the rate of

transmission so that all data will be received and retransmissions will

be minimized. See the figure for a simplified representation of window

size and acknowledgements. In this example, the initial window size for a

TCP session represented is set to 3000 bytes. When the sender has

transmitted 3000 bytes, it waits for an acknowledgement of these bytes

before transmitting more segments in this session. Once the sender has

received this acknowledgement from the receiver, the sender can transmit

an additional 3000 bytes. During the delay in receiving the

acknowledgement, the sender will not be sending any additional segments

for this session. In periods when the network is congested or the

resources of the receiving host are strained, the delay may increase. As

this delay grows longer, the effective transmission rate of the data

for this session decreases. The slowdown in data rate helps reduce the

resource contention.

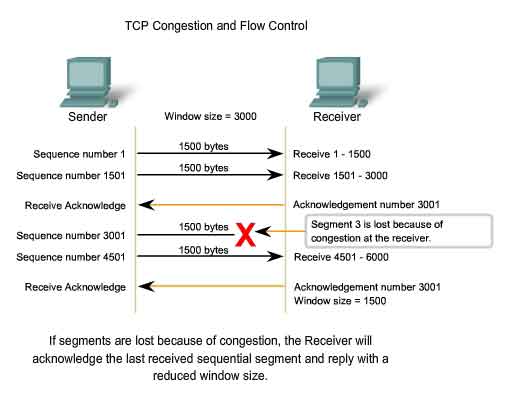

Reducing Window Size

Another

way to control the data flow is to use dynamic window sizes. When

network resources are constrained, TCP can reduce the window size to

require that received segments be acknowledged more frequently. This

effectively slows down the rate of transmission because the source waits

for data to be acknowledged more frequently. The TCP receiving host

sends the window size value to the sending TCP to indicate the number of

bytes that it is prepared to receive as a part of this session. If the

destination needs to slow down the rate of communication because of

limited buffer memory, it can send a smaller window size value to the

source as part of an acknowledgement. As shown in the figure, if a

receiving host has congestion, it may respond to the sending host with a

segment with a reduced window size. In this graphic, there was a loss

of one of the segments. The receiver changed the window field in the TCP

header of the returning segments in this conversation from 3000 down to

1500. This caused the sender to reduce the window size to 1500. After

periods of transmission with no data losses or constrained resources,

the receiver will begin to increase the window field. This reduces the

overhead on the network because fewer acknowledgments need to be sent.

Window size will continue to increase until there is data loss, which

will cause the window size to be decreased. This dynamic increasing and

decreasing of window size is a continuous process in TCP, which

determines the optimum window size for each TCP session. In highly

efficient networks, window sizes may become very large because data is

not being lost. In networks where the underlying infrastructure is being

stressed, the window size will likely remain small.

Details of TCP's various congestion management features can be found in RFC 2581.

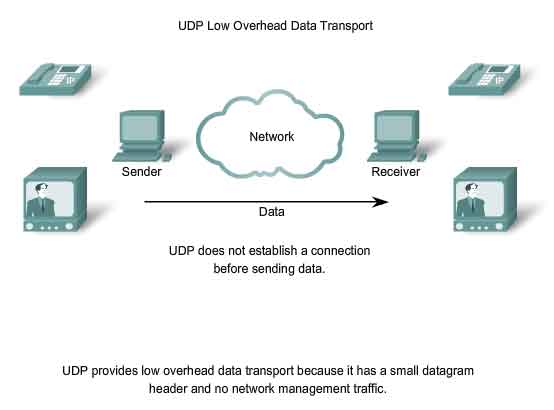

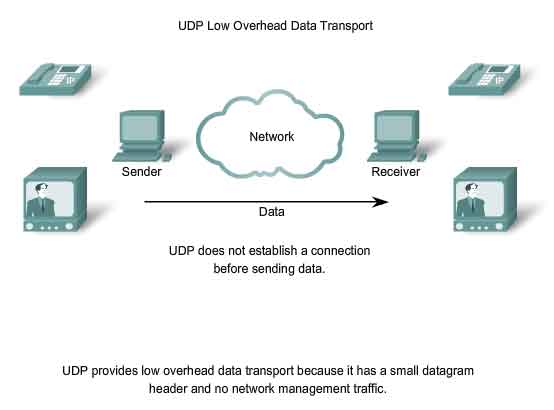

The UDP Protocol - Communicating with Low Overhead

UDP - Low Overhead vs. Reliability

UDP is a simple protocol that provides the basic Transport layer

functions. It much lower overhead than TCP, since it is not

connection-oriented and does not provide the sophisticated

retransmission, sequencing, and flow control mechanisms. This does not

mean that applications that use UDP are always unreliable. It simply

means that these functions are not provided by the Transport layer

protocol and must be implemented elsewhere if required. Although the

total amount of UDP traffic found on a typical network is often

relatively low, key Application layer protocols that use UDP include:

-

Domain Name System (DNS)

- Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP)

- Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP)

- Routing Information Protocol (RIP)

- Trivial File Transfer Protocol (TFTP)

- Online games

Some

applications, such as online games or VoIP, can tolerate some loss of

some data. If these applications used TCP, they may experience large

delays while TCP detects data loss and retransmits data. These delays

would be more detrimental to the application than small data losses.

Some applications, such as DNS, will simply retry the request if they do

not receive a response, and therefore they do not need TCP to guarantee

the message delivery. The low overhead of UDP makes it very desirable

for such applications.

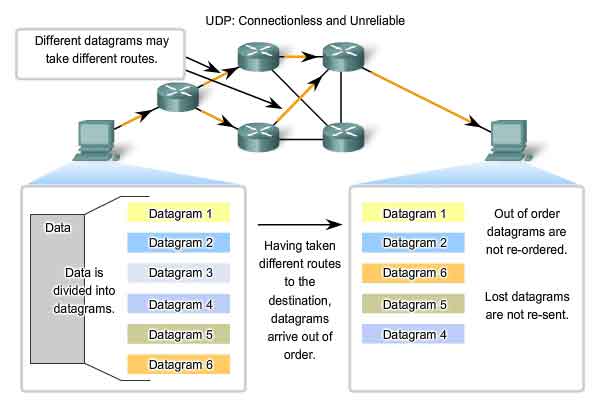

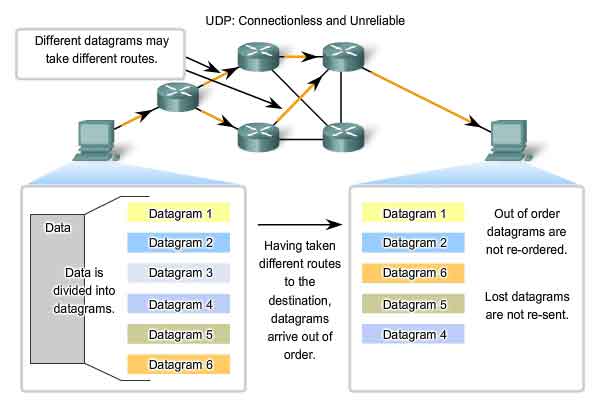

UDP Datagram Reassembly

Because UDP is connectionless, sessions are not established before

communication takes place as they are with TCP. UDP is said to be

transaction-based. In other words, when an application has data to send,

it simply sends the data. Many applications that use UDP send small

amounts of data that can fit in one segment. However, some applications

will send larger amounts of data that must be split into multiple

segments The UDP PDU is referred to as a datagram, although the terms segment and datagram

are sometimes used interchangeably to describe a Transport layer PDU.

When multiple datagrams are sent to a destination, they may take

different paths and arrive in the wrong order. UDP does not keep track

of sequence numbers the way TCP does. UDP has no way to reorder the

datagrams into their transmission order. See the figure. Therefore, UDP

simply reassembles the data in the order that it was received and

forwards it to the application. If the sequence of the data is important

to the application, the application will have to identify the proper

sequence of the data and determine how the data should be processed.

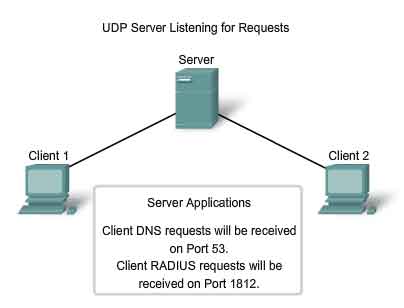

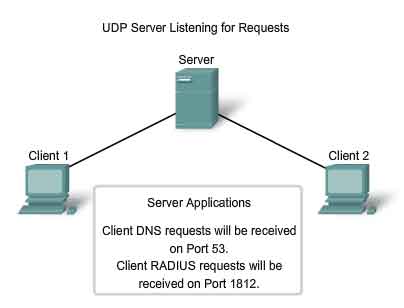

UDP Server Processes and Requests

Like TCP-based applications, UDP-based server applications are

assigned Well Known or Registered port numbers. When these applications

or processes are running, they will accept the data matched with the

assigned port number. When UDP receives a datagram destined for one of

these ports, it forwards the application data to the appropriate

application based on its port number.

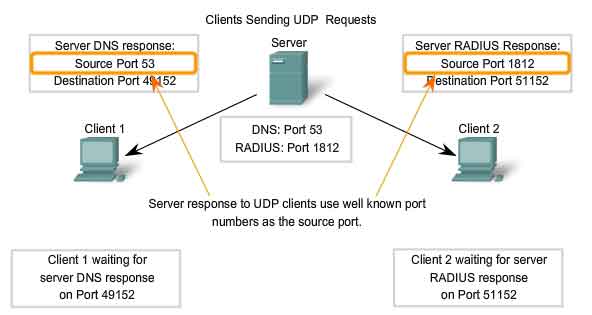

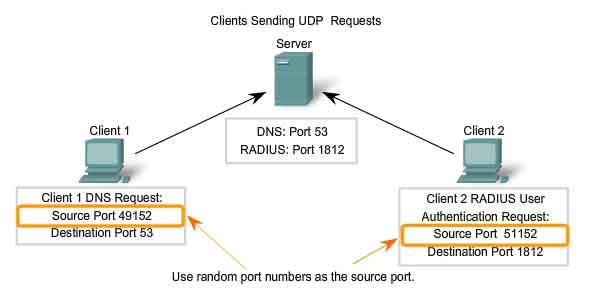

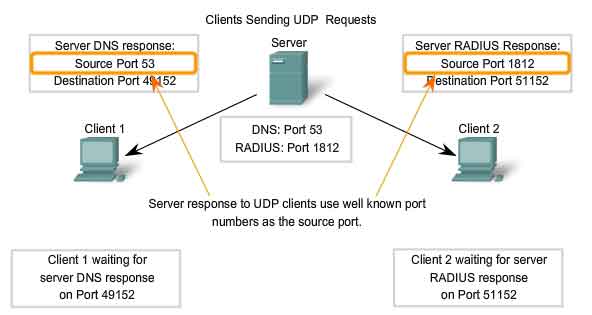

UDP Client Processes

As with TCP, client/server communication is initiated by a client

application that is requesting data from a server process. The UDP

client process randomly selects a port number from the dynamic range of

port numbers and uses this as the source port for the conversation. The

destination port will usually be the Well Known or Registered port

number assigned to the server process. Randomized source port numbers

also help with security. If there is a predictable pattern for

destination port selection, an intruder can more easily simulate access

to a client by attempting to connect to the port number most likely to

be open. Because there is no session to be created with UDP, as soon as

the data is ready to be sent and the ports identified, UDP can form the

datagram and pass it to the Network layer to be addressed and sent on

the network. Remember, once a client has chosen the source and

destination ports, the same pair of ports is used in the header of all

datagrams used in the transaction. For the data returning to the client

from the server, the source and destination port numbers in the datagram

header are reversed.